Spring 2024

By O. Victor Miller

Brad Yeomans’ boat rounded the wide curve, and the flat bottom of the Harris yawed, hissing as it bounded across a Jonboat’s wake, Fish, Fish, Fish. My fingernails were embedded in the wooden gunwales, and my hair was blown straight out in back like the crest of a pileated woodpecker. We were intermittently touching the water and, like a flat rock thrown sidearm, skipping the surface. I turned around to speak to Russell Martin on the seat behind me. Tears streamed from the corners of his eyes and his cheeks were flapping. It looked like his face was pressed against glass.

“Tell him to slow… down!” I screamed.

“What?”

“Slow… Down!”

“He’s got to stay up on a plane…to economize fuel.”

“But he’s… going… wide… open!”

“No, he’s not!… He’s cruising!”

“Brad twisted the throttle of the huge Evenrude another quarter turn, grinning devilishly. RPMs screamed like a dentist’s drill and the ride became absolutely smooth as the Harris lifted off water altogether. We were really economizing fuel now, having eliminated the drag of the water, sailing, like a hydrofoil, on a compressed blanket of air on the surface of the Altamaha River. Stumps flickered by like picket fences, and the wide banks were blurred by velocity and tears. We weren’t even leaving a wake. Only the blades of the propeller touched the water.

Suddenly Brad let off on the throttle and the momentum shoved us forward. The boat settled back into the water and glided up to a snag in the current he’d made by spearing a bamboo pole into the muddy bottom and tying on a Vidalia onion sack full of chum. He’d said the mullet gnaw holes in the bag to get at the chum, and sure enough the weave was loosened in the corners of the sack. He replaced the sack, this time a Guano bag, and filled it with shrimp breading he’d gotten from a friend who contracts it for his hogs from a seafood company.

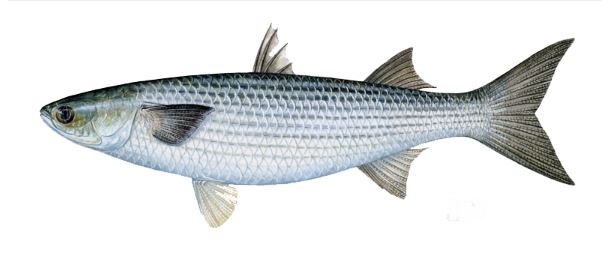

Photo couresy of Georgia Coastal Resources Division.

We were making preparations for a day of mullet fishing on the Altamaha. Russell and his son Allen had brought me to Gardi, Georgia, where we were to join Russell’s dad, Eldridge, and Eldrige’s running buddy, Franklin Smith, and Franklin’s two sons, Brian and Craig. Franklin was putting us up on his houseboat at Brad Yeomans’ Paradise Park Fish Camp at Boyle Island on Big River, which is an oxbow of the Altamaha and the Penholoway Creek. I’d never heard of catching mullet with worms and a cane pole, and I didn’t have a lot of confidence in Russell’s and Allen’s expertise. They’re nice folks, but Russell is president of REMAX of Albany. He and Allen both are spare-time members of rock-and-roll bands, and everyone knows that fishing and jukin’ aren’t necessarily complementary. But we were among the pretty blackwater rivers of the southeast Georgia coastal plains, a part of Georgia that still looks like Georgia is supposed to look, and these other “good old boys” we’d hooked up with looked like they might know what they were up to.

“Say the mullets ate a hole in the Guano sack?” said Brian Smith around a mouthful of delicious speckle trout Franklin and Eldridge caught in the sound at Darien, some twenty miles downriver. Brad nodded, spooning up some grits. Brian eyed his brother, who grinned.

“Maybe y’all better go out in Daddy’s metal boat tomorrow,” he said. “The mullets are liable to eat Eldridge’s wood boat right out from under him.” Brian had to work the next day and couldn’t fish.

Brad ignored Brian. “I’m going out about seven in the morning to freshen the chum. Anybody want to ride?”

“Not me,” I snapped. I didn’t want my drowned body ravaged by mullet.

“Well, I’ll come back for you after breakfast.”

In the middle of the night a skiff came by, rocking the houseboat, waking up Russell and Allen who had top bunks and caught most of the sway. I was awake, my blood still fizzing from Brad’s boat ride. I went out on deck and talked to some fishermen who had been running bush hooks baited with bream and had a boat load of flatheads, appaloosa catfish, which shone greenish gold in their gas lantern. The largest one looked like a nurse shark. It weighed thirty-seven pounds and had whiskers a foot long.

The next morning Brad came for us, and we followed him out in three boats. At a more leisurely speed, I was able to enjoy the scenery as we cruised down Big River and skipped out into the spectacular Altamaha. The water was low, exposing the baroque roots of enormous cypress, bay, and tupelo trees that doubled themselves in the bright green impasto of trees whose feet are always wet. We saw the white confetti of waterbirds in the distance and a floating seven-foot alligator eyeing a brace of wood ducks, who watched him back.

And we saw people too, folks fishing for mullet. They were lined up along the sandbars where the wide Altamaha crawled its last lap to the sea. There were families with big umbrellas and ladies with parasols, and even a few tents. Boys were standing waist deep in the current with cane poles and breambusters. Out from the humans were the telltale snags where Guano or Vidalia bags of chum were tied to poles shoved into the bottom. Some of the folks had lines running from the sand bar to the pole so they could yank the line once in a while to release chum.

And we saw people too, folks fishing for mullet. They were lined up along the sandbars , , ,

Our flotilla separated and Eldridge anchored at one of Brad’s snags, politely insisting that I fish the chum bag. He fished downstream and caught catching channel cats. I kept catching nothing. “You want to keep these cats?” he said.

“Yes sir, I sure do.” The catfish were smaller than bananas, the size I love to eat. I caught one hybrid, which Eldridge said we ought to release. But no mullet. Which didn’t surprise me. I still lacked solid confidence that mullet could be caught on a worm, but seeing all these people fishing for them had weakened my disbelief. A man seeing a couple hundred people standing around waiting for a flying saucer will glance up at the sky a time or two himself. Mullet are basically vegetarians; their diet consists of plankton, snails, and small organisms found in alga. They also suck up detritus off the bottom, hence the generic name Mugil (“sucker”). They have a gizzard to chew up the chunks and intestines seven times their length, so they can process a lot of mud, which they are full of. I’d read a lot about mullet, but I still hadn’t caught one. My great grandma Hinson from Hazlehurst used to catch them on lettuce, and the fishermen from Gardi tell me they’ll bite algae, dough balls or even a bare #6 gold hook. We used tiny red wigglers from Eldridge’s worm bed because nobody he knows has figured a good way to keep mud on a hook. But the key to catching mullet, if they could be caught, seemed to be getting a school of them to graze around in one place long enough to suck up whatever’s on your hook, and the key to that is chum.

“Maybe we ought to send Brad to Savannah for a mullet net,” I suggested. “He could be there and back in around six minutes.”

Rounding a wide curve on the horizon, we saw a thin funnel of spray coming up the river. The sky was too clear for it to be a waterspout, so we figured it was either a hydroplane taking off or Brad coming back to see how we were doing. It was Brad, flying toward us as though the mention of his name had conjured him. He cut his throttle about fifty yards out and coasted up to us. “How’s it going?”

“Nothing.”

“Nothing? Y’all better hook up with Franklin. Him and Craig got about a dozen. Go downstream to them. I’ll check up on Russell and Allen.” When he took off, the bow shot straight up. He leaned forward to keep from tumbling backwards over the transom. His Harris, a popular boat on the Altamaha, is a well crafted skiff with a flat bow plate that rises above the gunnels like the waxed front of a kid’s flattop.

Photo by Jimmy Jacobs.

Franklin and Craig were anchored on the inside of a wide bend where a sandbar dropped off into the molasses colored water. Craig had jumped out of the boat and was standing chest deep in the river. He was swatting vociferous minnows that were nipping him, and he was squirming and bouncing. “Ouch,” he said, “Yike.” He said the minnow bites feel like your leg when it goes to sleep, like low voltage electricity. The little fish, like mosquitoes, were drawing blood. So many swarmed the chum, Franklin and Craig had to load their lines with shot to get past the layer of them before they could clean the hooks.

“Maybe the minnows ate those holes in the onion bags,” I suggested.

But then Craig hooked a mullet that made his pole slap the water. He wrestled it over to the boat for his daddy to ice down, and I became a believer in less time than it took St. Paul to fall off his horse. “That’s an actual mullet!” I screamed, examining the drunken eyes and the white and pewter markings.

We tied up to Franklin’s jonboat, and he invited me to fish downstream from the Guano bag, where he was catching those blearie-eyed beauties one right after another.

“There’s plenty of room in this boat,” Franklin said ironically as I scrambled into his boat and sat in his lap.

“I wouldn’t want to crowd you,” I said, sweeping his cork aside with the tip of my pole. The encroachment paid off. My cork didn’t go under, but it palsied. “Pull it,” grinned Franklin. I did, and my line started singing and making figure eights. I pulled back and my bent pole started creaking. I stood up and shouted, “I’ve got one! I’ve finally hooked a mullet!” Franklin leaned away from me to stabilize the boat, and Craig dropped his pole and grabbed the side of the boat trying to steady us.

When a mullet bites, the cork just quivers and you snatch. A big one will make your line twang like a jewsharp. The ones we caught were about a cubit, the length of a man’s forearm. The one I caught was, like Eldridge’s channel cats, about the size of a banana. “You ought to throw that one back,” said Craig.

“Oh no,” I said as we weighed anchor, “I’m having this one mounted.”

We all met back at Paradise Park.

*****

“Pull? Son! A bass ain’t nothing!” said Russell, as he lifted his cooler to the deck of the houseboat. His fish gazed up from the ice with glassy-eyed placidity and the promise of succulence that only fresh fried mullet (pronounced moo-LAY by my gourmet wife Claire) can deliver to south Georgia cuisine. Franklin busied himself getting the grease hot, chopping up onion and bell pepper for the hushpuppies, and boiling grits. When he got finished, we ate fried mullet and channel cats until we, ourselves, were bleary-eyed, and there were enough mullet left over for me to soak in sugar and salt brine for my smoker.

After supper we listened to the waves chuck under the floor of the houseboat and watched the big bays and tupelos of Boyle Island darken as the sun went down. Soon we stole away one-by-one to the bunk beds to drift into sleep, rocked and cradled by the powerful river that moved beneath us to the sea.

Vic Miller is a retired educator, having taught at Darton College in Albany. After that career he sailed his boat Kestyll to Panama to live aboard among the Kuna Indians. While there he fly fished and did mortal combat on occasion with the local crocodiles. His award-winning writing appears periodically in Gray’s Sporting Journal. Vic is a member of the Georgia Outdoor Writers Association. His latest book, Buzzard Luck, won first place in that organization’s 2023 Excellence in Craft competition for outdoor themed books. Buzzard Luck is available from Amazon.com. Vic can be contacted at kestyll@hotmail.com.