Summer 2024

Article and photos by Jon Wongrey

The eastern sun had not long hued golden when it was quickly masked by mouse-colored clouds as Clarence Harris, at 85 known simply as “Mr. Clarence,” clucked his tongue twice to the double-rigged mules.

Mr. Clarence at the reins.

With the gentle tap of the reigns the wagon slowly moved forward – and back to an era of southern aristocratic bird hunting – on the 3,000-acre Southwind Plantation in what is known as “the bobwhite quail belt” near Bainbridge in Decatur County.

The morning of the first of a three-day “bud” hunt, as bobwhites were once called in the Deep South, the land was covered with a white frosted rind and autumn’s fields were beginning to enter a time of slumber.

Now there was a man, his name I cannot remember, whom I recall said that he had been a young boy in Poland when the Germans marched in. He eventually immigrated to the United States, was educated, and as the story goes, became quite successful.

He was quite the gentleman and “right off the bat,” invited me to hunt with him. I explained that I was a writer on assignment and would try to hunt with him later in the hunt, but first I must get my photos and notes “put to bed,” before picking up a gun. But I promised him that I would shoot alongside him before the hunt ended.

The hunt began shortly after breakfast and by mid-morning ashen clouds began blocking the morning’s sun in this land of long-leaf pines and knee-high broom straw. I was once again amid southern grace, culture, bird dogs and bobwhites, also once called “partridge” or “patridge.”

Before loading into the wagon, I heard the mention of “snow!” I knew enough about southwest Georgia to know that it seldom ever snows. “When?” I asked.

Smiles were plentiful, but no words were spoken. But snow it did in southwest Georgia that day and for the remainder of my time at Southwind. “Snow!” you ask. Yes, but a different kind of snow. This I will explain but not now, for I must continue the story.

A brace of well-honed English pointers was released from the dog pen and right away they went to demonstrating their breeding, training, and natural instincts. They hunted not as spaniels, but not as far and wide-ranging field-trial English pointers.

Having grown-up in a small southern town in mid-South Carolina, unofficially celebrated as the bird dog capital of my state, I was around great dogs, trainers and quail. Wild birds then were as numerous as grains of sand on a beach, but no more.

While there are a few wild coveys on Southwind, the quail here, because of the volume of shooting , are pen-raised and released to be hunted among the longleaf pines.

Though there is an artificial aspect to shooting pen-released birds, preserves protect the meager wild bird community, which cannot sustain heavy hunting pressure.

There is no skepticism when it comes to the hunting abilities of Southland trained bird dogs.

On point!

The two English pointers inhaled the spoor of quail, quartered the land and went on point. Two hunters walked-up behind the pointers. Six birds whirred up. It was then I witnessed Georgia snow as four birds folded in mid-flight releasing a shower of feathers called “Georgia snow.”

All the while the elderly man from Poland, and whose words were pronounced with a hint of the old country, was off in another area of the plantation hunting and still very much alone.

I finished the day with what I thought were some fine photos, but not yet what I wanted to illustrate the story.

That evening at dinner, or as I still refer to as “supper,” the lonely hunter again asked me to join him on tomorrow’s hunt. I once again had to respectively decline, explaining that I first had to make sure that I was content with my photo package. “When I’m satisfied that my photo shoot is complete, I’ll walk and shoot alongside of you,” I said.

“I understand,” he said in fractured English. “But on third day you shoot with me, right?”

“On the afternoon of the third day, I will hunt with you?”

A faint smile dented his narrow face, “Okay, after lunch on third day we hunt?”

“Yes, after dinner (dinner in many areas of the South is what others call lunch).

On the morning of the second day another dog was stirred into the mix, a small black English cocker spaniel called Toby, whose hunting ambition was contagious and a pleasure to watch as he slashed the fields using 10 times the steps of the long-legged pointers. When I first saw Toby, he looked to be no more than three months old. Turned out that Toby was two years old.

The two pointers scented the intoxicating redolence of “buds” and “stamped” the find. Toby was sent in to flush the birds holding tight in the thick wire grass.

Twelve birds flushed in a spray of brown feathers. Shots echoed through the woodlands. Four birds “puffed’ nicely. Breast feathers floated down in geometric design.

Toby returned with a rooster firmly fixed in his small mouth and did so with a zest that would have rivaled a kid finding the golden-colored egg on Easter morning.

Toby with the retrieve.

“These English cockers,” Butler said, “are passionate, and I don’t know how we ever hunted without them. They bring a lot to the hunt.”

That evening at supper I again saw the man who was born in Poland and whose name I ashamedly cannot recall. He right off the bat asked if I was, “through with my photo shoot?”

“Will be through at mid-day tomorrow.” And before he could squeeze out a word, I said, “Meet you at the wagon.” Which I did.

Though not English, his attire was that of a European Baron and he carried a fine 26-inch Purdy double barrel 20-gauge with the right barrel improved choke and the left barrel modified. I was shooting a 26-inch Beretta over-and-under 20-gauge improved choke on top and modified on bottom.

On a plantation preserve it does not take long to find birds. Two whirred up. I fired twice knocking both birds down. I did this three times in a row: six shots and six birds. My new friend had yet to fire a shot.

When this happened for a fourth time, he no longer walked close to my side when the dogs pointed, but began ranging away from me.

Closing in on the covey.

And while “release” quail provide an extension of the “real” experience.

At the end of the hunt, I shot a total of 16 times and killed 16 quail. I was an old “wild bird” shooter, when quail were plentiful. My friend had expended numerous shells and only had a handful of birds.

He said not one word to me on the way back to the lodge. When we dismounted the mule-drawn wagon, he spoke: “Jon, from now on, I hunt alone!”

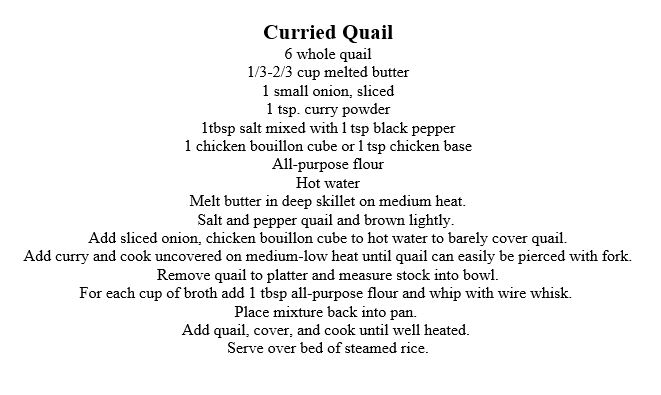

AFTER THE HUNT